All about emojis

In person, you can easily tell someone’s mood based on their body language and how they speak. But that’s much more difficult with text alone. Emojis are a great way to add tone to a piece of text and also help make text-based conversation feel more casual, relaxed, and fun. Thanks to emojis, we can chat with much more real emotion than you might get by being careful about your word choice or by including just the right number of exclamation marks and periods at the end of a sentence.

Where did emojis come from?

Emojis (or “emoji,” which is technically the correct pluralization) are characters that are displayed as small images on devices that support them. This makes them different from emoticons which are loosely defined, purely text-based sequences of characters, such as <3 or ಠ_ಠ.

The term emoji comes from the Japanese words e- (meaning “pictures”) and -moji (meaning “character”) since the original emojis were created by Japanese cell phone carriers in the 1990s. Eventually, the Unicode Consortium stepped in and came up with the standard set of emojis that we use today, although that set is frequently updated and expanded from the original version.

Emoji sequences

As Unicode characters, emojis are encoded on most platforms as UTF-8 characters which are rendered into images on platforms that support them. Emojis can also be made up of sequences containing more than one character, although they’ll still be displayed as a single image as long as the emoji sequence is supported by the current platform. Some sequences are made by following an existing emoji with a special modifier character while others are made by combining multiple emojis.

When typing and reading these characters, most devices will usually try to hide the fact that you’re actually working on multiple characters, but when processing text with code, you have to be aware of these cases. Recently, I solved a bug involving this behavior (MM-22079).

Mattermost tries to map Unicode emojis to the corresponding system emoji (which normally appears when using an emoji’s short name such as :taco:), but previously, it would only look for the first character of the sequence, so it would accidentally display the wrong version of emojis. For example:

- 👋🏾 (waving hand, medium-dark skin tone) would appear as 👋 (waving hand, no skin tone)

- 🙅♂️ (man gesturing no) would appear as 🙅 (either woman gesturing no or person gesturing no, depending on your browser’s emoji support)

The code that handles that has since been fixed so that it properly considers all characters in the sequence.

Skin tones

The most common emoji sequences are called emoji modifier sequences. An emoji modifier sequence is simply made by taking a supported emoji and following it with a special character called an emoji modifier.

Currently, emoji modifier sequences are used to change the skin tone of a supported emoji from the default yellow to a variety of human skin tones. The five modifiers that are used in the emoji specification are based on the Fitzpatrick Scale of skin tones.

On a system that doesn’t support a given modifier sequence, you should see the original emoji followed by a colored rectangle matching the given skin tone, indicating that the emoji was intended to have a specific skin color.

Flags

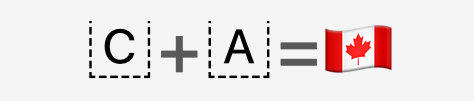

Another type of emoji sequence are flag sequences used for the flags of different countries. Flag emojis are made up of regional indicator characters which correspond to the 26 letters of the Latin alphabet (from 🇦 to 🇿). Each flag is represented as a pair of regional indicators corresponding to the country’s two-letter country code.

On a system that doesn’t support a given flag, you’ll see the letters indicating the country code.

Zero-width joiner sequences (gendered emojis, family emojis, etc.)

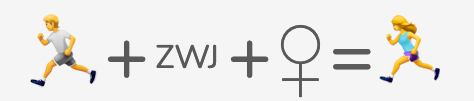

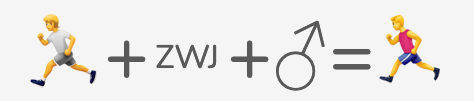

The zero-width joiner (ZWJ) is a special invisible character that’s used to form more complicated emoji sequences. Certain emojis can be combined together by placing a ZWJ between them to create a new emoji that combines elements of both of the original ones.

The most common place you’ll find a ZWJ is in gendered emojis. Originally, many of the emojis representing jobs (e.g., firefighter, judge, and doctor) were assigned genders. But it was later decided that those emojis should be gender-neutral by default. To specify a gender for those emojis, the gender-neutral emoji can be followed by a ZWJ and then the female or male sign characters to produce a female or male version of the emoji.

But these sequences can become more complicated and include more emojis under certain circumstances. For example, the emojis for different types of families are made up of an emoji representing each member, all combined together with ZWJs.

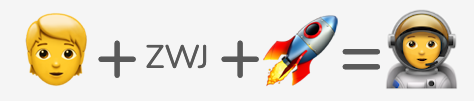

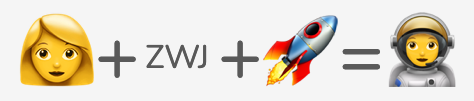

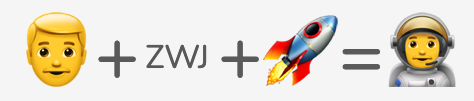

Some other emojis can be made of more abstract combinations. For example, the astronaut emojis are made by combining person/man/woman and rocket.

There are also a few other ZWJ sequences that can be used to flip an emoji or change its hair color, but those are newer and have less support.

Closing thoughts

Emojis are constantly evolving as each new version of the specification includes new emojis and changes to existing ones. At the time of writing, Emoji 13.1 is fairly new, and many vendors are still working to support it. By the time you read this, there may be many more types of emojis and emoji sequences to explore.

If you want to know more about the latest emojis, or you just enjoy reading technical specifications, you can read the latest version of the emoji specification.

Alternatively, if you want to chat about emojis or anything else Mattermost-related, feel free to join us in the ~Developers channel on the Mattermost community server.